Three Tales of Adventure in the West

12/08/2012 05:50PM ● By Christina FreemanBy Harriet Freiberger

SHORT NIGHTS OF THE SHADOW CATCHER

The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis

by Timothy Egan

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, NY 2012

Hard cover 412 pages $28

20 B&W photos

Timothy Egan, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer for the New York Times, chronicled the life of Edward Curtis, creator of the 20-volume series, “The North American Indian.” In writing about the West, Egan says, “It only seems logical to try to tell some of the stories of the longest-lasting tenants of a place I love.”

Edward Curtis collected those stories. In 1899, he began the project that preserved the last remnants of Native American traditions, rapidly vanishing in the face of ordered destruction. Success came quickly to the man who dug clams to survive as a child and whose formal schooling ended with the sixth grade. Curtis’ work with glass-plate negatives produced portraits during Seattle’s Gilded Age and was widely known around the Pacific Northwest.

When Curtis was age 30, a meeting and subsequent photographs of Angeline, last surviving child of Chief Seattle, was the start of “the largest, most comprehensive and ambitious photographic odyssey in American history.”

The “Big Idea” became the driving force of a lifetime: to photograph all intact Indian communities left in North America, “to capture the essence of their lives before that essence disappeared.” Ethnographer, anthropologist and historian, Edward Curtis was 61 years old when he finished Volume XX in 1929.

The acclaim that followed publication of early volumes, support from President Theodore Roosevelt, and J.P. Morgan’s financial investment counted for nothing during the final 23 years of the photographer’s life. Curtis vanished, like his work, from the American scene. He never earned any money from his Big Idea, but left a monumental legacy that today garners immense respect. A private sale in 2009 brought $1.8 million for a single Curtis set. More importantly, the old language and customs survive among tribal communities because of his recordings and writings.

Timothy Egan lets his readers accompany Edward Curtis into the lands of the first Americans. It is a compelling journey.

Author’s note: The Denver Art Museum owns one complete copy of the original volumes, which were published one-by-one from 1907-1930.

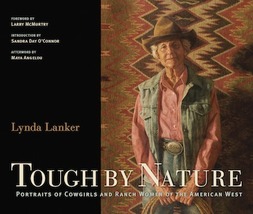

TOUGH BY NATURE

Portraits of Cowgirls and Ranch Women of the American West

by Lynda Lanker

Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene 2011

Oregon State University Press

Hard cover 132 pages $39.95

Foreword by Larry McMurtry

Introduction by Sandra Day O’Connor

Afterword by Maya Angelou

Lynda Lanker received her degree in art from Wichita State University and has lived for the last 34 years in western Oregon. “Tough By Nature” was published in conjunction with an exhibition that is currently being shared with museums around the country. With a rare combination of her own artistic skill and the spoken words of the women she interviewed, Lanker has recorded the reality of women’s place in the American West.

What began as a collection of landscapes and portraits became a learning process that drew upon the full resources of the artist’s versatility. For 19 years, through 13 states, Lynda Lanker journeyed to those outlying spaces where cowgirls are more than fancy hats and shiny boots. In charcoal drawings, oil pastels, egg tempera, pastel and pencil, stone and plate lithography, 49 women take their places in and on the land, letting the urban-oriented reader stretch into an otherwise unreachable world. The women speak for themselves.

A fourth-generation New Mexican rancher says, “People who think cattle are bad for the land don’t know what they’re talking about.”

A 32-year-old wife, mother and rancher tells of the satisfaction of working with new life and “realizing, at a very young age, that dying is part of the cycle.”

They are modern and traditional, some with master’s degrees, one creating promotional videos of a successful breeding program, and another winning awards for excellence in range management.

Lanker’s subjects live where they work. They handle cattle and horses, work like hired hands and know how to take care of themselves. “Cowgirls” represent the hundreds of women in the West who run cattle ranches, compete in rodeos, train horses, take care of families, advocate for the environment — and their way of life.

“I learned from them, and they changed me … the resilience, character, and quiet strength of these extraordinary women will be with me forever,” Lanker says.

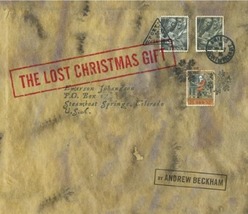

THE LOST CHRISTMAS GIFT

by Andrew Beckham

Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2012

Hard cover 40 pages $29.95

“The Lost Christmas Gift” transports readers to a long-ago time in the mountains of Colorado’s Western Slope. Two days before Christmas, on a traditional search for the tree that will be “just right,” 11-year-old Emerson Johansson and his father become lost during a snowstorm on Rabbit Ears Pass.

The mysterious happenings of the night that follows are brought to mind again many decades later, when a package, having been somehow lost in the mail for 70 years, arrives, ironically, on December 23.

The old, now brittle paper with its antiquated postage stamps contains an exquisite gift sent by Johansson’s father from a place some miles from the front line of World War II in Europe. Photographs made by the boy with his new camera during the night they had shared, pictures thought to be lost those many years, now reappear, awakening memories.

Present and past overlap, and in the telling, three points of view create a magical connection with what has been. The boy, now old and a great-grandfather of four, recognizes himself in the drawings and watercolors. A second layer is interwoven through the pages of the extraordinary gift itself, and finally author Andrew Beckham entices the reader into a suspended state of disbelief and a wondrous Christmas story.

Nine years ago, during his annual ski touring visit of the backcountry near Rabbit Ears Pass, Beckham took photographs that would become part of the story Johansson asked him to write.

Beckham chairs the visual art department at St. Mary’s Academy in Englewood, and his work is represented in collections around the country.