Aspen Diaries

07/01/2005 01:00AM ● By Kelly Bastone

Summer 2005:

Aspen Diaries

by Kelly Bastone

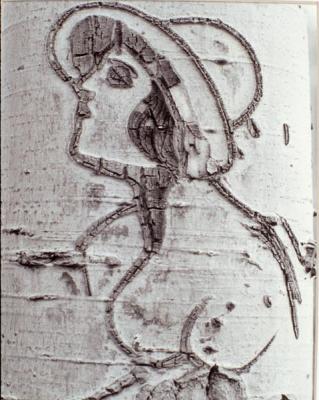

One glimpse of the sexy carvings left by a century of sheepherders Spying valentines like “MH+JT” scratched into aspen bark is too commonplace to be titillating, but one glimpse of the sexy carvings left by a century of sheepherders may leave you breathless — if not a little hot under the collar. Hinman Park, Buffalo Pass, California Park — places in Routt County where sheep have been grazed since the late 1800s, contain whole galleries of aspen art. Sketches are commonly found on older trees, along the edges of meadows where the herder could sit in the shade, yet be near his flock. Some carvings are religious in nature; others, like an enormous mosquito, offer insight into the day-to-day hassles of herding sheep. But most are of nude women, and are usually accompanied by the artists’ names, dated from long ago. Lady With A Hat. Photo by Ken Proper Sheepherders aren’t the only aspen artists. Along with ubiquitous lovers, hunters have also been known to carve trees, often sketching elk or deer into the bark. Aspen art isn’t exclusive to Routt County. It’s common throughout California, Nevada, Arizona – anywhere aspens grow. But there’s a unique poignancy to the herders’ carvings. With no companions but sheep, herders created woodland nymphs to keep them company and remind them of the comforts of home, much as soldiers cherished pinup girls. Most of the artists are nolong gone, and many of these sketches are nearing 100 years old, yet the images still speak volumes about the life and longings of their creators. Those longings could be mighty at times, and some carvings are suitable for adult audiences only. A feare assaultingly graphic, and even though the tree’s growth over time enlarges the drawings and makes them rounder, some body parts were obviously super-sized in the artists’ original versions. Even so, the herders’ art reveals much more than just sexual frustration. “Sometimes they just tear at your heart,” explains Angie KenCairn, heritage specialist for the U.S. Forest Service, who studies aspen art, or arborglyphs, in the Routt National Forest. As an archaeologist, Angie learns a great deal from the herders’ tendency to date their work, and the messages often yield valuable information about historic construction projects and stock drives. She is also touched by herders’ cravings for human contact. “They were lonely men. That’s obvious from the sheer number of women they drew.” Yet their yearning for company goes beyond the sexual. “One carving reads, ‘Es trieste a vivir solo,’ (It’s sad to live alone). That’s tough. It’s why herding sheep isn’t a job that many people want to do,” she says.

Lady With A Hat. Photo by Ken Proper Sheepherders aren’t the only aspen artists. Along with ubiquitous lovers, hunters have also been known to carve trees, often sketching elk or deer into the bark. Aspen art isn’t exclusive to Routt County. It’s common throughout California, Nevada, Arizona – anywhere aspens grow. But there’s a unique poignancy to the herders’ carvings. With no companions but sheep, herders created woodland nymphs to keep them company and remind them of the comforts of home, much as soldiers cherished pinup girls. Most of the artists are nolong gone, and many of these sketches are nearing 100 years old, yet the images still speak volumes about the life and longings of their creators. Those longings could be mighty at times, and some carvings are suitable for adult audiences only. A feare assaultingly graphic, and even though the tree’s growth over time enlarges the drawings and makes them rounder, some body parts were obviously super-sized in the artists’ original versions. Even so, the herders’ art reveals much more than just sexual frustration. “Sometimes they just tear at your heart,” explains Angie KenCairn, heritage specialist for the U.S. Forest Service, who studies aspen art, or arborglyphs, in the Routt National Forest. As an archaeologist, Angie learns a great deal from the herders’ tendency to date their work, and the messages often yield valuable information about historic construction projects and stock drives. She is also touched by herders’ cravings for human contact. “They were lonely men. That’s obvious from the sheer number of women they drew.” Yet their yearning for company goes beyond the sexual. “One carving reads, ‘Es trieste a vivir solo,’ (It’s sad to live alone). That’s tough. It’s why herding sheep isn’t a job that many people want to do,” she says. Bear and horse carving, showing herders' challenges. Photo by Ray Heid Yet since about 1895, the seasonal work of herding sheep has attracted men willing to trade companionship for money. Some were Basque or Irish, but most came from Mexico and NeMexico to work for the big sheep outfits of southern Wyoming and western Colorado, which sent the herders and their flocks to Routt County’s excellent pastureland. During turn-of-the-century “range wars” between cattlemen and wool growers, herding was as dangerous as it was lonely, as herders risked getting shot or hanged by Routt County cattle ranchers determined to keep sheep off their range. But because the job included food and camp-style housing as well as a paycheck, sheepherding remained attractive to men desperate for a way to return to their families with full pockets. Far from home and with no human audience, sheepherders have made aspens their vehicle for communication. Eloy Trujillo, who carv-ed a number of trees on Buffalo Pass near Summit Lake, developed a recognizable style. He apparently favored silk stockings, and often included a garter on his lady’s thigh, yet there’s an undeniable artistry in Trujillo’s use of line, and his figures are tastefully rendered. In Slater Park, Odi Lan took an entirely different approach, drawing figures so explicit they prompted Forest Service employee Patrick Goot to claim, “Odi put the ass in aspen art.” Another artist dispensed with the striptease altogether to declare, “Yo pienso,” (I think) – a statement affirming the carver’s very existence. Still other trees simply share a joke, or pass along information (like “spring” with an arropointing to the water source). Even Elvis is enshrined in aspen bark – possibly alluding to the artist’s musical taste. The fate of these carvings depends on the trees’ life span, which for aspens is about 100 years. Much of the oldest art has actually been discovered on standing dead or fallen trees, and the forest service is striving to document these carvings before they disappear. “They’re a cultural resource,” Angie emphasizes. “Defacing them in any way is a federal offense. Anyway, people should be respectful of those who came before them and respect their legacy.”

Bear and horse carving, showing herders' challenges. Photo by Ray Heid Yet since about 1895, the seasonal work of herding sheep has attracted men willing to trade companionship for money. Some were Basque or Irish, but most came from Mexico and NeMexico to work for the big sheep outfits of southern Wyoming and western Colorado, which sent the herders and their flocks to Routt County’s excellent pastureland. During turn-of-the-century “range wars” between cattlemen and wool growers, herding was as dangerous as it was lonely, as herders risked getting shot or hanged by Routt County cattle ranchers determined to keep sheep off their range. But because the job included food and camp-style housing as well as a paycheck, sheepherding remained attractive to men desperate for a way to return to their families with full pockets. Far from home and with no human audience, sheepherders have made aspens their vehicle for communication. Eloy Trujillo, who carv-ed a number of trees on Buffalo Pass near Summit Lake, developed a recognizable style. He apparently favored silk stockings, and often included a garter on his lady’s thigh, yet there’s an undeniable artistry in Trujillo’s use of line, and his figures are tastefully rendered. In Slater Park, Odi Lan took an entirely different approach, drawing figures so explicit they prompted Forest Service employee Patrick Goot to claim, “Odi put the ass in aspen art.” Another artist dispensed with the striptease altogether to declare, “Yo pienso,” (I think) – a statement affirming the carver’s very existence. Still other trees simply share a joke, or pass along information (like “spring” with an arropointing to the water source). Even Elvis is enshrined in aspen bark – possibly alluding to the artist’s musical taste. The fate of these carvings depends on the trees’ life span, which for aspens is about 100 years. Much of the oldest art has actually been discovered on standing dead or fallen trees, and the forest service is striving to document these carvings before they disappear. “They’re a cultural resource,” Angie emphasizes. “Defacing them in any way is a federal offense. Anyway, people should be respectful of those who came before them and respect their legacy.” This carving reveals two faces. Photo by Ray Heid So what’s the difference between this “cultural resource” and garden-variety graffiti? Angie maintains that “MH+JT” is not exactly less valuable than the sheepherders’ carvings, and that recent aspen art tends to document different patterns of forest use, such as recreation. “It’s all part of our history, but I’d hope people wouldn’t just run off into the woods and carve up every tree they see,” she says. For one thing, encountering aspen carvings can ruin the feeling of wilderness discovery, of being the only person to have arrived in a particularly pristine part of the woods. Most folks don’t mind sharing the landscape with a buxom beauty, but seeing “Leroy was here” can be deflating. Carving into the aspen bark also harms the tree. By rupturing its “skin,” carving invites fungus and bacterial infections into the tree, as well as infestations of insects and other pests. Novice carvers (the valentine types) tend to gouge deeply into the wood, leaving ugly scars that can ultimately kill the tree. But out of concern for the aspens, or because they knea lighter touch made for better artwork, many sheepherders etched their designs into only the first or second layers of bark. And they’re still etching. The sheep industry reached its peak in the 1920s, and much of the aspen art dates from that time. But flocks are still grazed on the Routt National Forest and during the summer months, it’s not unusual to see sheepwagons in Buffalo Park or near the Wyoming border. Herders nocome from as far away as Chile, Peru and even Mongolia, where the news of Colorado job opportunities spreads by word of mouth and lures fathers away from their families in order to support them financially. A handful of herders seek jobs in Rawlins during the off-season, but very fehave settled down or started nelives in America. Instead, most take their paychecks home to wives and children in Mexico or South America. Their work here may be temporary, but sheepherders have left an enduring legacy on the trees, turning aspens into pale pages of a fascinating diary. It’s uncensored stuff, so visit the trees and be forewarned. Kelly Bastone is a local writer and exhibits curator for the Tread of Pioneers Museum.

This carving reveals two faces. Photo by Ray Heid So what’s the difference between this “cultural resource” and garden-variety graffiti? Angie maintains that “MH+JT” is not exactly less valuable than the sheepherders’ carvings, and that recent aspen art tends to document different patterns of forest use, such as recreation. “It’s all part of our history, but I’d hope people wouldn’t just run off into the woods and carve up every tree they see,” she says. For one thing, encountering aspen carvings can ruin the feeling of wilderness discovery, of being the only person to have arrived in a particularly pristine part of the woods. Most folks don’t mind sharing the landscape with a buxom beauty, but seeing “Leroy was here” can be deflating. Carving into the aspen bark also harms the tree. By rupturing its “skin,” carving invites fungus and bacterial infections into the tree, as well as infestations of insects and other pests. Novice carvers (the valentine types) tend to gouge deeply into the wood, leaving ugly scars that can ultimately kill the tree. But out of concern for the aspens, or because they knea lighter touch made for better artwork, many sheepherders etched their designs into only the first or second layers of bark. And they’re still etching. The sheep industry reached its peak in the 1920s, and much of the aspen art dates from that time. But flocks are still grazed on the Routt National Forest and during the summer months, it’s not unusual to see sheepwagons in Buffalo Park or near the Wyoming border. Herders nocome from as far away as Chile, Peru and even Mongolia, where the news of Colorado job opportunities spreads by word of mouth and lures fathers away from their families in order to support them financially. A handful of herders seek jobs in Rawlins during the off-season, but very fehave settled down or started nelives in America. Instead, most take their paychecks home to wives and children in Mexico or South America. Their work here may be temporary, but sheepherders have left an enduring legacy on the trees, turning aspens into pale pages of a fascinating diary. It’s uncensored stuff, so visit the trees and be forewarned. Kelly Bastone is a local writer and exhibits curator for the Tread of Pioneers Museum.